Into people’s noses: investigating past respiratory health to reconstruct a society’s response to urbanisation

PhD candidate Maia Casna explores the impact of diseases on past societies.

Today as in the past, disease affect everybody globally. They do not only confine us in bed or within hospital walls; their presence affects how we function within our social group and, as a consequence, they influence the way a society works as whole. If we are ill (or a large group of people around us is), then certainly our life is going to be compromised. Palaeopathology (“the study of disease in the past”) explores the health challenges our ancestors had to face before us in order to help us better understand the ones we are facing today.

When I was a bachelor student, my anthropology professor once told the class the set of disease that characterizes any human society is an expression of the interaction between individuals and the environment (natural and/or artificial) in which that society is immerged. This means that paleopathology can add to the present archaeological knowledge by highlighting existing links between the way people lived their lives and the traces left on their bones by the diseases they suffered from. Starting from this assumption, I shaped my own PhD research around the role that respiratory health may play into the assessment of people’s living conditions. As our respiratory system is in direct contact with the air we breathe, our respiratory health will actively change basing on the risk factors the environment we live in will expose us to (e.g., air pollution, industrial smoke, bacteria).

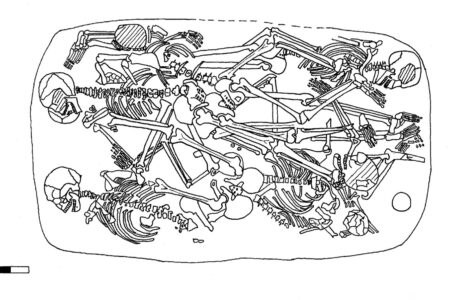

On human bones, it is possible to observe traces of respiratory disorders on the ribs and within the paranasal sinuses (small air-filled spaces in the skull that purify breathed air). In my research, I will examine the bones of more than 1000 individuals from all over the Netherlands, looking for small lesions and bone deposits that might reveal the presence of respiratory conditions such as sinusitis and pneumonia.

Respiratory health and urbanisation

The intensification of the urbanisation movement during the late medieval period in all northern Europe has, among other things, resulted in a greater number of people exposed to poorly ventilated, unhygienic living and working environments. As societies became more complex and reached high population densities, the risk factors for respiratory disease likely increased. Even though a limited number of studies in palaeopathology have focused on the link between urbanisation and respiratory disorders, the general consensus seems to point out that people’s respiratory health sensitively worsened with the rise of urban economies.

While it is easy to imagine such scenario in our trope of medieval London, things get more complicated when we think about the Netherlands. Here, the urbanisation process was more nuanced and gradual than it was in other European cities, suggesting that social disparities in health and welfare were not as extensive as we are used to think. Probably due to such as small impact, Dutch urbanisation has been almost exclusively studied through written historical sources. Building on this previously-acquired knowledge, I aim to include the voices of those whose life is not recorded on history books, such as lower social classes and minorities like women, children and foreigners. Assessing how these people responded to the urbanisation process will contribute to the building of a more complete history of the Netherlands, possibly encouraging more researchers in taking up the challenge of using bioarchaeological data to understand our social past.

A mirror for today's health

However, despite my interest in social history, one of my main research interests remains the use and relevance of archaeology in today’s world. In the past two decades, several clinical studies have focused on the consequences that rapid urbanisation is having on people’s health, highlighting the raise of social inequalities, epidemics and non-communicable diseases such as Parkinson's disease, strokes and Alzheimer's disease.

Today, urbanisation and overpopulation of centres are more active than ever and, despite being the subject matter of many studies, they continue to represent a serious threat to human welfare. Only in the Netherlands, respiratory disorders affect 12% of the population annually, causing impairment in 30% of cases. However, environmental and cultural risk factors are considered as secondary in clinical research, whose focus seem to be almost exclusively set on air pollution. In this context, working on a big sample size as the one offered by archaeological skeletal remains is a unique opportunity to test different hypotheses otherwise hardly assessable on a modern population.

Respiratory infections have scourged humankind since its appearance and, at present, even with the huge availability of antibiotics, they are among the most recurring causes of death in developing countries. With my research, I am trying to promote the concept of the social dimension of disease. Revealing the link between cultural and biological processes, I aim to get more researchers involved with considering the challenges human health faced in the past as a tool to interpret the ones we are facing in the present.

0 Comments