Talking Stones: Surveying Ancient Carvings in Northern Pakistan

Alexander Mohns participated in an applied archaeology workshop in Pakistan. Through this workshop he got very rare access to the petroglyphs scattered througout the region, many still undocumented and under threat.

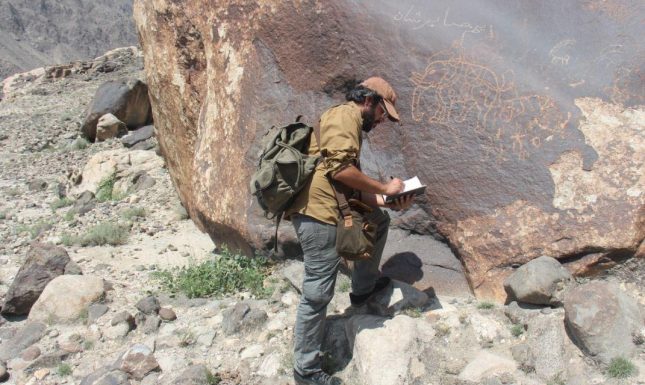

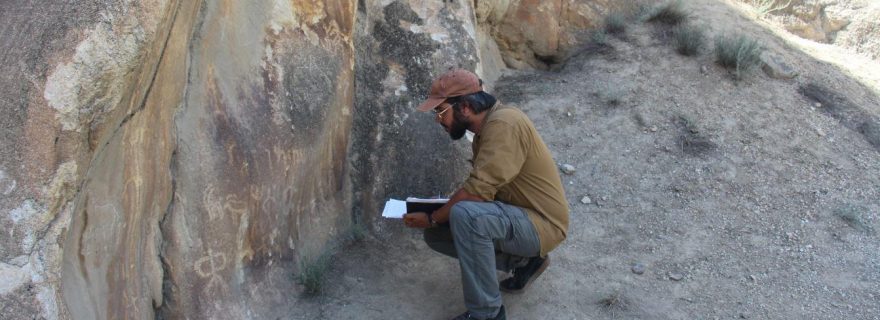

As part of Marike van Aerde’s project ‘Routes of Exchange, Roots of Connectivity’ at Leiden University, I was able to participate in an applied archaeology workshop in Gilgit-Baltistan in Northern Pakistan in July 2019. This workshop provided a very rare access to the petroglyphs scattered throughout this region, of which many are still undocumented and under threat at the moment.

For my BA thesis at Leiden University, I analyzed the (so far known) dataset of Buddhist rock carvings found in the region, so this was an amazing opportunity for me to come face to face the carvings, their context in the landscape and, especially, to meet the people who are working in the region at the moment.

Gilgit-Baltistan is located close to where the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and Himalayan mountain ranges meet. It is a rugged landscape in a harsh environment but with an indescribable beauty that is found within the land itself as well as the people who inhabit it. Travelling to Gilgit was quite an experience, flying over the snowcapped Himalayas was a view I won’t easily forget.

The workshop in Gilgit was hosted by the Karakoram International University (KIU), Dr. Jason Neelis from Wilfried Laurier University in Canada and Dr. Murtaza Taj from the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). The main techniques that were utilized during this workshop included, 3D scanning, Photogrammetry, GIS mapping, and Reflectance transformation Imaging (RTI). Alongside the digital techniques used for working on the petroglyphs there were also sessions where epigraphy was discussed and practiced, since many of the petroglyphs are inscriptions in Kharoshti and Brahmi scripts.

Throughout my time at the workshop I was given information on the different aspects of using each different digital technique for the documentation of the petroglyphs. We attended lectures and were taken through the region for field trips. We visited sites such as the KIU archaeological park as well a larger petroglyph site at Hunza, a town close to Gilgit, and towards the end of the workshop we visited an undocumented site with many petroglyphs close to Alam Bridge. These fieldtrips were an excellent opportunity to see the carvings I had worked on during my Bachelors and actually see then in their original context and their natural environment.

There is always a large difference between looking at archaeological material published in academic literature versus actually seeing the material in its original context. By seeing the archaeology in its original environment you can start to get a better idea of how it functions within the landscape. When dealing with petroglyphs such as the ones along the Upper Indus, it is very useful to see how these carvings are situated along the main rivers that run through the region (the Indus and the Gilgit river) since they give deeper insight as to where the ancient people of this region would have travelled for their trade routes.

The techniques that were taught during the workshop are currently the most useful and applicable methods available for the documentation of these carvings and their contexts. However, most of these techniques are aimed only at the documentation of these petroglyphs and not towards interpreting them in the larger context of ancient trade networks. A deeper analysis of these rock carvings and the patterns that they produce in terms of distribution and location can give us better insights as to how these ancient trade routes functioned and what kind of infrastructure may have been present along these trade networks.

Overall, the experience of working together with the local people at the workshop was a very satisfying one. I was able to discuss different archaeological issues with people who actually live there and have first hand experience with the issues occurring in the region. In particular there are several threats to the petroglyphs located in the Gilgit region due to large infrastructural projects and political issues. Some of the carvings have been painted over due to political agendas, and the construction of the Diamer-Basha dam in the region also threatens the preservation of the carvings. It was great to see that these carvings have meaning to the people of the region and that young scholars are eager to learn about their preservation. Hopefully with a new generation of enthusiastic scholars the history of these carvings will be preserved and treasured. The contacts I made this summer have already led to new collaborations with Van Aerde’s project at Leiden University, as well, with a new publication coming up later this year that I will also co-author.

The workshop raised awareness about the different aspects of preservation regarding the petroglyphs along the Upper Indus, and for me it was a great opportunity to be in the field in the area that I have specialized in and to make new connections with local scholars and share ideas with them. It has also been an important step towards new connections between our research project at Leiden University and the archaeology community in Pakistan.

Read more about the research project Routes of Exchange, Roots of Connectivity.

0 Comments