Recycle your Neolithic axe!

Last month the Dutch government installed a 15 cent deposit on cans in order to promote recycling. Recycling has been part of human behavior since early prehistory. In prehistoric research especially the recycling of metal has received much attention.

But recycling was also important in earlier periods. In our recent study (which was published open access in Lithic Technology) we devoted ourselves to the study of recycled flint axes. This study was part of the research project: Putting Life into Late Neolithic Houses, Investigating domestic craft and subsistence activities through experiments and material analysis (NWO AIB.019.020)

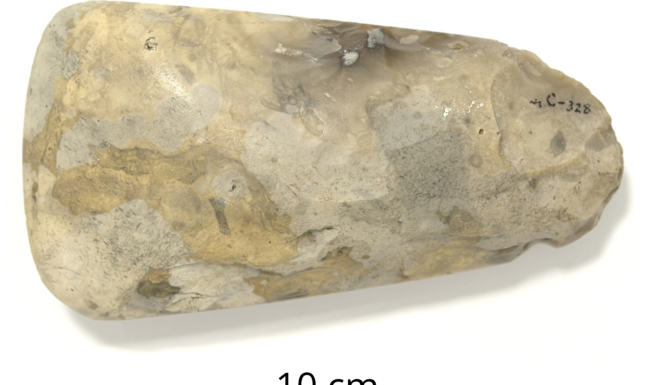

On many Vlaardingen Culture (3400-2500 BC) sites in the western Netherlands large quantities of flint axe fragments are found. These are often reworked into scrapers, borers and other tools. In the western Netherlands flint is not locally available, thus all flint had to be imported from other regions. Flint axes were often imported in a ready made state from flint mining centers (such as Spiennes, Rijckholt and Hesbaye) in Belgium and the south of Limburg. These axes are beautifully knapped and fully ground oval axes, often referred to as “Buren axes” (see figure 2). When these axes break they still provide a sizable flint nodule. Although this nodule cannot be used anymore as an axe, it can be recycled by turning it into a flake core to create other tools. We often find these tools and flake cores (see figure 3). We can recognize them as ‘axe fragments’ because they still have a remnant of the ground outer surface of the axe.

A major unresolved issue was that we did not know whether this ground surface will always be present when you recycle these axes. We can imagine that at some point during the reduction sequence flakes (from the inside of the axes) are struck off which no longer have this ground or polished surface. If they would lack this ground surface they cannot be identified as axe fragments.

To test this we setup an experiment. We used four replicated flint axes, three of which we broke before reuse. The other axe we kept whole until we started flaking. Surprisingly, most of the axe fragments did no longer had a ground surface. Only 190 out of the 466 axe fragments (larger than 1 cm) still had a remnant of a ground surface. This was only 41% of the total assemblage. This meant that when axes are reused only 41% of the axe fragments will still be recognizable as an axe fragment. We decided to use this percentage to better assess the importance of recycling on known Vlaardingen Culture settlements. Especially, on the sites Voorschoten Boschgeest and Hekelingen III this yielded surprising results. In Voorschoten Boschgeest 12,8% of all the flint artefacts still displayed a ground surface, on Hekelingen III 17,9% of the artefacts displayed a ground surface. If we assume that this only represents 41% of the actual amount of axe fragments on these sites we can suggest that ca. 31% of the flint from Voorschoten Boschgeest and almost 44% of all the flint from Hekelingen III originally came from flint axes.

The experiments highlight that we have greatly underestimated the importance of the use of recycled flint axes in the Vlaardingen Culture. The experiments also provided new angles for future studies. Although some sites seemed to rely heavily on the reuse of flint axes, other sites hardly made use of this resource. In Voorburg Hadriani for example we estimate that only 4,4% of the assemblage consisted of flint axes. We tend to assume that recycling is the logical result of consumption. But if that is the case we would expect that these percentages are more or less consistent amongst these sites. Why would people in Hekelingen III consume ten times more axes than the people in Voorburg Hadriani? Perhaps this distribution is not simply a logical result of the consumption of flint axes. As it is often the case in science, the study brought up as many questions as it could solve.

See for more information the project website.

0 Comments

Add a comment