Tracing syphilis and mercury in skeletal remains from a late medieval Dutch infirmary

Syphilis, one of the most prevalent sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), continues to affect millions worldwide. Thanks to antibiotics, the prognosis for infected individuals has vastly improved, but in the past it was a life-threatening and stigmatized disease with widely feared treatment methods.

Syphilis is one of four infectious diseases caused by bacteria of the genus Treponema, and can be transmitted sexually or in utero from mother to unborn child. If left untreated, syphilis progresses through three consecutive stages with distinctive symptoms. Most severe is the tertiary stage, linked to seriously debilitating symptoms such as cardiovascular and neurological complications. Additionally, severe and destructive changes in the skeleton may occur during the tertiary stage, which provides osteoarchaeologists with a unique opportunity to identify potential cases of syphilis in the archaeological record.

Syphilis and skeletons

The most recognizable change in the skeleton is a distinctive deformation of the skull with a worm-eaten appearance, known as caries sicca. Other bones in the skeleton can also be affected by syphilis infection, showing changes such as excessive new bone growth, destructive cavities, or a combination of both. In the tibia, new bone growth can produce a forward-bowed appearance, a phenomenon referred to as “sabre-shin” due to its shape. Despite these telltale signs, syphilis and other treponemal infections can be difficult to identify in skeletal remains, because they are difficult to distinguish from other infectious diseases.

Mercury: remedy or poison?

From the late 15th century onwards, syphilis quickly spread through and greatly affected the European population. In a desperate attempt to mitigate rising infection rates, medieval medics sought out many, but not always effective, remedies, of which the toxic heavy metal mercury was most popular. The use of mercury in syphilis treatment was based on the symptoms caused by its toxic nature, as mercury induces extreme salivation and urination, believed to expel syphilitic particles from the body. Due to the high dosages that were administered to achieve these effects, mercury poisoning was likely a common occurrence among syphilitic patients. Various historical imageries (fig. 1) and sayings, such as “for a night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury” or “for a pleasure, a thousand pains”, express the uncomfortable nature of repeated and prolonged treatment sessions.

Syphilis at St. Gertrude’s infirmary in Kampen, the Netherlands

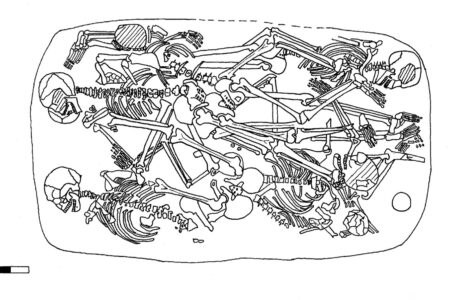

For my research, I analysed human skeletal remains from St. Gertrude’s infirmary to assess the potential impact of syphilis and its treatment on the local population. The infirmary provided care for the sick, poor, and elderly in the late medieval city of Kampen, the Netherlands (fig. 2). Its cemetery, operational from approximately 1381 to 1611, was excavated by a team of archaeologists from Leiden University in 2014, which recovered the skeletal remains of 89 individuals. Upon further examination, evidence for syphilis could be identified in a few individuals. This provided a unique opportunity to investigate how the disease affected patients and whether evidence for mercury treatment at the site could be identified in the archaeological record.

For this study, the skeletal remains received an additional osteological analysis, this time with a more specific focus on identifying skeletal changes that signify a potential syphilis diagnosis. Using a scoring system to classify lesions consistent with, suggestive of, or diagnostic for syphilis, my research identified more individuals that were potentially affected by syphilis.

In total, 6.3% of individuals showed lesions diagnostic for syphilis, which is markedly higher than has been reported for other late medieval and early modern sites from the Netherlands. The potential impact of this disease becomes even more clear when taking into account individuals that showed multiple lesions suggestive of syphilis, for which the prevalence rate was established at 12.4%. These findings show that citizens in Kampen, especially the poor and sick, may have been at a higher risk to contract this infectious disease than their national peers. It is hypothesized that the city's role as an international trading hub contributed to these high prevalence rates, as it facilitated increased contact between people from diverse regions and caused episodes of severe overcrowding.

Tracing mercury in skeletal remains

In addition to diagnosing syphilis in the bones, I was also interested in the methods used to treat the disease. To investigate the possible use of mercury at St. Gertrude’s, a combination of different trace elemental analytical techniques were employed: portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (pXRF) (see banner image) and Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) on bone, and Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX) on tooth plaque. The aim of this pilot study was to see whether these methods could detect traces of mercury in archaeological skeletal remains, in order to potentially identify mercury treatments for syphilis at St. Gertrude’s infirmary.

Unfortunately, both pXRF and SEM-EDX analyses were not able to produce quantified and comparable mercury concentrations in bone or tooth plaque. Interestingly, while the ICP-MS analyses revealed traces of mercury in a small subsample, the results were not conclusive enough to confirm widespread or systematic use of mercury treatments.

What’s next?

The paleopathological investigation of St. Gertrude’s infirmary formed the pilot study for my next research project, which will explore the prevalence and potential impact of syphilis across multiple late medieval and early modern hospital sites throughout the Netherlands. Through an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating osteological, biomolecular, and historical methods, the aim is to not only gain a better understanding of the disease’s distribution, but also to illuminate the lived experiences of individuals affected by this stigmatized infectious disease.

References and further reading

Baker, B. J., Crane-Kramer, G., Dee, M. W., Gregoricka, L. A., Henneberg, M., Lee, C., Lukehart, S. A., Mabey, D. C., Roberts, C. A., Stodder, A. L. W., Stone, A. C., & Winingear, S. (2020). Advancing the understanding of treponemal disease in the past and present. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 171(S70), 5–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.2...

Hackett, C. J. (1976). Diagnostic criteria of syphilis, yaws and treponarid (treponematoses) and of some other diseases in dry bones. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-...

Harper, K. N., Zuckerman, M. K., Harper, M. L., Kingston, J. D., & Armelagos, G. J. (2011). The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: An Appraisal of Old World pre-Columbian evidence for treponemal infection. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 146(S53), 99–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.2...

Klomp, M. (2017b). Myosotis, in de schaduw van het Sint Geertruidengasthuis: Archeologisch onderzoek tussen Boven Nieuwstraat en Burgwal. (4; Archeologische Rapporten Kampen, pp. 1–334). Gemeente Zwolle.

Tampa, M., Sarbu, I., Matei, C., Benea, V., & Georgescu, S. R. (2014). Brief history of syphilis. Journal of Medicine and Life, 7(1), 4–10.

0 Comments

Add a comment